Iron in Human Physiology

Iron is an essential mineral that plays a critical role in human physiology. Within the human body, iron functions as a key component of hemoglobin, the protein responsible for transporting oxygen throughout the bloodstream. This transportation of oxygen is fundamental to cellular respiration and energy production, processes that occur continuously to maintain normal bodily functions.

The body's requirement for iron and related nutrients varies based on age, sex, and activity level. Understanding the biological mechanisms by which dietary iron contributes to normal physiological processes is important for informed dietary choices. Different population groups have varying levels of nutritional needs, and a diverse diet helps support the body's natural requirements.

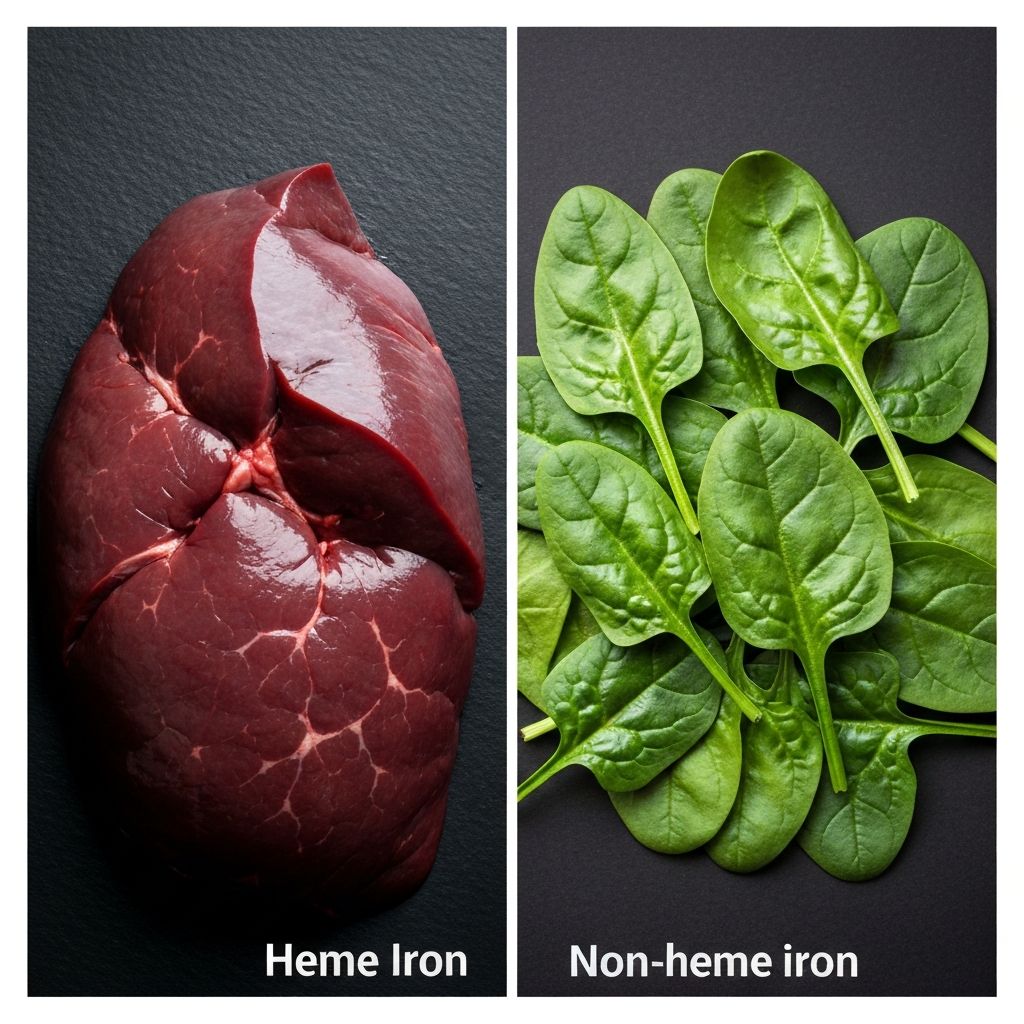

Key fact: Iron exists in two primary forms in nature—heme iron, found in animal sources, and non-heme iron, found in plant sources. These forms differ in how they interact with digestive processes and absorption mechanisms in the human body.

Key Iron-Related Nutrients

Several minerals and vitamins work in conjunction with iron to support normal biological processes. The interactions between these nutrients affect how the body handles iron uptake and utilization. Understanding these relationships provides context for the role of diverse nutrition in maintaining normal physiological function.

| Nutrient | Role in Iron Metabolism | Interaction Type |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | Enhances absorption of non-heme iron; acts as reducing agent | Enhancer |

| Copper | Required for iron transport and utilization in hemoglobin synthesis | Facilitator |

| Zinc | Competes with iron for absorption; balance important for normal function | Competitive |

| Vitamin B12 | Supports red blood cell formation and oxygen transport processes | Supportive |

| Folate | Essential for erythrocyte (red blood cell) production | Essential |

Product Examples: Natural Iron Sources

Nature provides diverse sources of iron and related nutrients. These examples represent common, everyday foods available in various markets and used in everyday cooking. The following products exemplify how iron and supporting nutrients are naturally distributed in food sources.

Beef Liver

Heme Iron Source

Beef liver contains highly absorbable heme iron. One serving provides significant quantities of iron along with vitamin B12, copper, and selenium. The bioavailability of heme iron is notably high, meaning the body can effectively utilize the iron present in this source.

Spinach

Non-Heme Iron Source

Raw and cooked spinach provide non-heme iron along with vitamin C, which enhances iron absorption. Spinach also contains folate and other minerals. When prepared with vitamin C sources, the iron bioavailability increases through biochemical mechanisms.

Lentils

Legume Iron Source

Lentils provide non-heme iron and plant-based protein. They also contain fiber and polyphenols. When combined with vitamin C-rich foods or copper sources, the nutritional profile is enhanced for better utilization.

Heme vs Non-Heme Iron

Heme iron is derived from hemoglobin and myoglobin found in animal tissues. This form is bound to a porphyrin ring structure, which makes it less subject to inhibiting factors in the digestive tract. Heme iron absorption rates typically range from 15-35%, depending on various physiological conditions.

Non-heme iron is found in plant sources and fortified foods. This form is more susceptible to inhibitory compounds such as phytates, tannins, and calcium, which can bind to iron and reduce its absorption. However, enhancers such as vitamin C can significantly increase non-heme iron bioavailability.

The distinction between these two forms is important for understanding how dietary choices contribute to overall nutritional intake. Neither form is inherently "superior"—both play a role in dietary diversity and are part of traditional diets across various cultures.

Vitamin C Enhancement

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) plays a significant role in iron absorption, particularly for non-heme iron. This vitamin functions as a reducing agent, converting ferric iron (Fe3+) to ferrous iron (Fe2+), a form that is more readily absorbed in the small intestine.

Foods rich in vitamin C include citrus fruits, berries, tomatoes, bell peppers, and broccoli. Consuming these sources alongside non-heme iron sources can substantially increase the bioavailability of dietary iron through chemical processes occurring during digestion.

This enhancement effect is one example of how food combinations contribute to the overall nutritional value of a meal—a principle observed in traditional cooking across many cultures.

Copper and Iron Interaction

Copper is an essential mineral that plays a direct role in iron metabolism. Specifically, copper is required for the function of ceruloplasmin, an enzyme that oxidizes ferrous iron (Fe2+) to ferric iron (Fe3+), enabling iron to bind to transferrin for transport throughout the body.

Natural sources of copper include shellfish, nuts, seeds, legumes, and organ meats. A deficiency in copper can impair iron metabolism even when dietary iron intake is adequate. This demonstrates the interconnected nature of mineral metabolism in human physiology.

The balance of copper and iron is maintained through complex regulatory mechanisms. Neither nutrient should be prioritized in isolation—understanding their interdependence is essential for comprehensive nutritional awareness.

Zinc and Iron Balance

Zinc and iron share similar absorption pathways in the intestine, which means they can compete for uptake. Both minerals are essential for numerous physiological processes, and their balance is important for optimal nutritional status.

High intakes of one mineral can theoretically reduce absorption of the other, but in the context of varied, typical diets, this competition is generally not problematic. The body's regulatory mechanisms help maintain adequate levels of both minerals when dietary intake is diverse and sufficient.

Sources of zinc include meat, shellfish, legumes, nuts, and seeds—many of which also provide iron or copper. This overlap in food sources makes it natural to obtain balanced quantities of these minerals through typical dietary patterns.

Natural Iron Absorption Factors

Iron absorption is influenced by multiple physiological and dietary factors. Understanding these factors provides context for how the body processes dietary iron and why nutritional diversity is valued across cultures.

Absorption Enhancement Factors

- Vitamin C: Reduces non-heme iron and increases absorption efficiency

- Animal proteins: Enhance absorption through meat factor (MFP)

- Organic acids: Citric and lactic acids improve bioavailability

- Gastric acid: Necessary for iron solubilization and absorption

Absorption Inhibition Factors

- Phytates: Found in grains and legumes; can bind iron

- Tannins: Present in tea and coffee; reduce absorption

- Calcium: At high levels, may compete for absorption

- Polyphenols: Some plant compounds can inhibit uptake

Optimal Food Combinations

Traditional food combinations often reflect empirical knowledge about nutrient interactions. Pairing iron sources with vitamin C-rich foods, preparing foods to reduce phytate content through cooking or fermentation, and consuming varied protein sources all represent strategies that maximize nutritional value.

For example, a meal combining beef liver, broccoli (vitamin C), and a small amount of whole grain provides heme iron, non-heme iron enhancement, copper, zinc, and supporting vitamins—demonstrating how balanced meals naturally integrate multiple supportive nutrients.

Daily Iron Context

Iron requirements vary by age, sex, and individual factors. Adult males typically have daily iron requirements, and the body maintains iron homeostasis through regulated absorption and recycling of iron from expired red blood cells.

Dietary intake recommendations reflect population-level needs, and individual requirements may vary. The concept of "daily value" provides reference points for understanding the iron content of foods, but individual dietary patterns and preferences are equally important.

A diverse diet naturally incorporates multiple iron sources and supporting nutrients, making nutrient balance an organic outcome of varied food choices rather than something requiring precise calculation.

Food Combination Examples

Breakfast: Eggs with whole grain toast and fresh oranges—combining heme iron (eggs), non-heme iron (whole grains), and vitamin C (citrus) for enhanced absorption.

Lunch: Spinach salad with beef, pumpkin seeds, and lemon dressing—pairing non-heme iron (spinach), heme iron (beef), zinc (seeds), and vitamin C (lemon) for synergistic nutrient delivery.

Dinner: Lentil soup with tomatoes and a side of broccoli—combining non-heme iron (lentils), vitamin C (tomatoes, broccoli), and fiber for a balanced meal that supports typical dietary patterns.

These examples demonstrate practical approaches to creating nutritionally dense meals that naturally support iron and mineral intake through food diversity rather than isolated supplementation.

Common Natural Iron Sources Overview

Animal Sources (Heme Iron): Beef, poultry, fish, shellfish, organ meats (liver, kidney), eggs

Plant Sources (Non-Heme Iron): Legumes (lentils, chickpeas, beans), whole grains, nuts and seeds, dark leafy greens (spinach, kale), dried fruits (apricots, prunes)

Fortified Foods: Cereals, breads, and pasta with added iron compounds

These sources are widely available in markets worldwide and form the basis of traditional diets across diverse cultures and geographic regions. The variety naturally ensures intake of iron, copper, zinc, vitamin C, and other supporting nutrients.

Scientific Iron Facts

- Iron exists in ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric (Fe3+) oxidation states, each with different absorption characteristics

- Heme iron absorption rates are 15-35%; non-heme iron rates are 2-20%, with bioavailability influenced by dietary factors

- Ceruloplasmin (copper-dependent enzyme) is essential for iron oxidation and transferrin loading

- The body recycles approximately 20-25 mg of iron daily from expired red blood cells

- Iron-regulatory hormones (such as hepcidin) maintain systemic iron balance through feedback mechanisms

- Phytic acid (phytate), found in grains and legumes, forms insoluble complexes with iron when pH is neutral or high

- Organic acids enhance non-heme iron absorption by lowering pH and maintaining iron in reduced form

- Polyphenol compounds in tea and coffee inhibit non-heme iron absorption through chelation

Explore More Information

This educational resource provides introductory information about natural iron sources and related nutrients. The scientific understanding of iron metabolism, nutrient interactions, and dietary approaches to maintaining adequate nutrition is based on extensive research across multiple disciplines.